EDOM 10: a history of habits and a multitude of moods

or "March Moodness"

MOOP matter

Before I serve you the newsletter entrée, please take note of these Magical Office of Peace notices:

Council 13

Councils are informally formal meetings where I present current efforts at the Magical Office of Peace and gather feedback. If you are sufficiently curious, and your schedule allows, I would love you join :)

These meetings are on 1st and 3rd Wednesdays, hosted on Discord.

The next Council (No. 13) is 3 April 2024 at 15:00 PDT / 18:00 EDT

Space Suckers date moved to end of May

As mentioned in EDOM 8, I am in a sci-fi clown show called “Space Suckers from Outer Space,” along with several other EDOM readers!

The dates for the show have moved. Space Suckers will now run Friday, 31 May through Sunday, 2 June at 20:00.

The show is at Church of Clown in San Francisco, Calif. Tickets will be available soon.

Thank you for noticing. Enjoy your main course.

a history of habits and a multitude of moods

For over three years I tracked my personal habits and mood on a daily basis in a spreadsheet. Today I am publishing these records.

I’m making them public because:

it gives me a reason to analyze my habits and mood for my own enlightenment;

it is a way for me to express my emotions, which have often been difficult for me to share with others;

it offers an insight into my life that proves I am not perfect. You might think that’s very obvious, but I’m concerned not everyone is as keen as you are;

it is a case study of a mental health journey;

and it serves as an example or template that others might find useful for examining their own lives.

origins of the worksheet

In November 2020—back when I was Walking for (regular) President—I noticed I was often consumed by modern-day distractions while avoiding healthier activities. I thought that tracking my habits would help me actually do my habits—or at least the activities I wanted to do often enough to consider them habits. So I made a spreadsheet as a visual record and reminder of this mission. I called it the “Warrior Worksheet”.1

I started by tracking wether or not I meditated, practiced yoga, or worked out. Over time, I expanded the worksheet to include other routines and actions. Did I floss that day? Did I journal? Did write down something I was grateful for? I also kept track of things I didn’t do in an effort to curb habits I wanted to reduce, like watching youtube, reading reddit, or scrolling on my phone.

However, the most instructive item I tracked was not behavior, but mood. It turned out to tell a story of my mental health—or frequently, illness—that I might not have realized otherwise. Paired with the tracked habits, I saw how my behaviors did—or did not—relate to my feelings of joy, okay-ness, depression and thoughts of self-harm.

a peak at the sheet

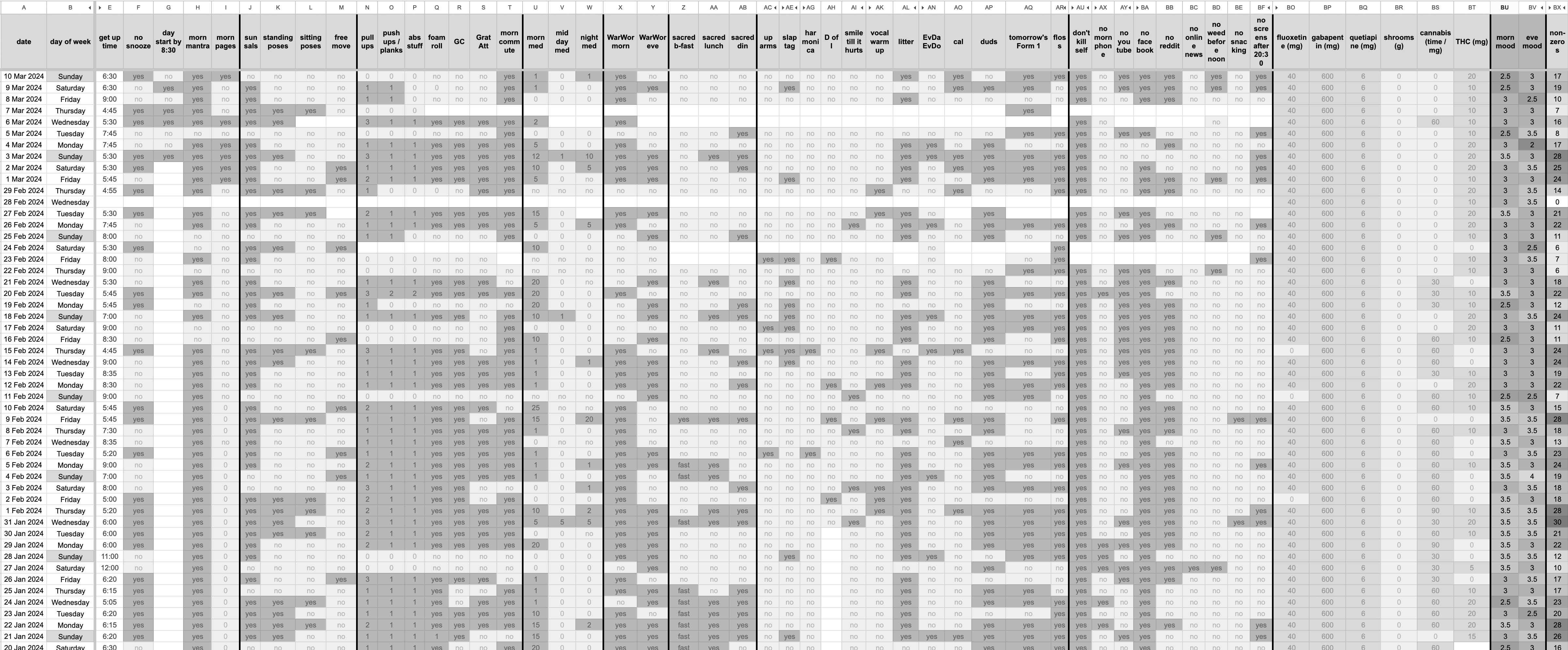

You can take a look at the Warrior Worksheet here in real-time. But you can also see a snapshot below. You may notice there are quite a few columns. Almost 60 that I fill out these days, and 89 including things I don’t track anymore.

I have a binary way of counting my habits. For most of the columns I record either a “yes” or “no”. Yeses get colored dark grey and noes are colored light grey. A few other columns use numbers: a zero counts as no and anything greater than zero is a yes.2 Cells that are empty and white indicate where I did not make a record.

Without having much understanding of what each of the columns represent, we can can squint and look at darker patches and say “Stephen James was consistently doing some habits in those couple of weeks.” When we can see spotty areas, me might say “Those regions are consistent with when Stephen James was inconsistent.”

While the collective records of the Warrior Worksheet offers little meaning from a visual standpoint, fortunately they look clearer through a statistical lens.

quantifying of the qualitative

I used a number scale to rate my mood daily. As you might imagine, using self-reported numbers to describe my emotional state has its limitations in terms of encompassing the complexity of my human experience. However, that’s what I did because I figured it was better than nothing.

At first I decided to record my mood on a scale from 1 to 5, where larger numbers represent more positive state of mind. After less than a month, I was having days that I rated as “ones,” but then I had days that were even worse. So I expanded the scale to start at zero. Fortunately, I haven’t had to go into negative numbers.

The scale that I use looks like this:

5 - VERY GOOD: I feel incredible, ecstatic or elated. I might be on drugs.

4 - GOOD: I am quite happy.

3 - OK: I feel neither particularly good, nor bad.

2 - BAD: I feel depressed.

1 - VERY BAD: I am having feelings of deep depression with some suicidal thoughts.

0 - VERY VERY BAD: I am extremely despondent, and am having strong and frequent thoughts of suicide.

To account for changes in my disposition throughout the day, I record a 0 to 5 twice: once in the morning and once in the evening. Also, I make ratings in half-unit steps to account for the the granularity of in-between feelings.

Anyway, what does it look like if we plot the raw data of my mood over time?

Here, each bar represents a single mood record (of which there are two-per-day). While the plot is noisy, it’s clear that over the first 6 months of records there was a relatively high variation in my mood rating (high of 5, low of 0), while in the most recent six months the variation is a lot smaller (high of 4, low of 2). Why is that? I’ll discuss more later, but the short answer is psychotherapy and medication.

In an effort to reduce the noise and see overall trends, let’s look at a 7-day rolling average.3 (Though its important to note that the averaging diminishes the apparent range of my mood on any given day.) In this plot, I drew a line at a mood of “3” (i.e. “okay”) to better visualize when my disposition was (on average) above or below average.

The smoothing of the data reveals an interesting pattern in the first months of my records. Let’s zoom in and take a look at that:

There is regular up and down cycle with a period of around 16 to 21 days. I noticed this pattern within the first four cycles. I was very surprised to see it. The cycle didn’t correspond to anything that was happening in my life. It didn’t match a schedule I had, the frequency was too high to be related to the phase of the moon, and I had no indication that I was menstruating.

Noticing this pattern changed the way I thought about my mental health. Frequently when I was stewing in my melancholy, I would point to anything unfortunate in my life and say “That is why I feel so shitty.” But now I wondered, maybe I’m just ill-tempered because of some internal cycle and not because of an external cause. I suspected that my dips into depression were something that could be treated with medication.

caring for my mental health

Without detailing my mental health history, I’ll say I’ve had bouts of depression and suicidal thoughts over the course of two decades (since I was 16). For most of that time I did not share my feelings with friends or family, and did not consult with mental health professionals. I certainly did consider antidepressants.

The short story of why I was anti-antidepressants is that (1) I felt they would be a crutch I would depend on, (2) I felt I ought to defeat my depression via a disciplined lifestyle, and (3) I wanted to focus “natural” medicines like psychedelic mushrooms and ayahuasca.

My resistance to prescription medication softened because (1) I realized that walking with a crutch is better than hobbling in pain, (2) while I still think self-discipline will be a boon to my mental health, there’s no reason it has to be the only tool I use, and (3) while my experiences with psychedelic substances would improve my mood for days or weeks afterwards, they weren’t resulting in lasting long-term effects. Also, my therapist was taking SSRIs and she seemed to be pretty well-adjusted.

So in April 2021, I got a prescription for bupropion4 (also known as Wellbutrin). After more than two months with no effect, I stopped. The non-improvement confirmed my notion that anti-depressants weren’t going to help me. But I gave them another shot after some particularly bad days in August 2022. I began a course of fluoxetine (an SSRI marketed as Prozac), and it did have an effect.

Within the first two days I had a body feeling—a comfortable fullness in my chest, like a mild MDMA experience—that told me something was happening. That feeling eventually went away, but what came was a more pleasant frame of mind. About six weeks after starting the initial daily dose of 20 mg, we increased my dosage to 40 mg. I’ve been on that course for over a year. It has helped, and I have the data to prove it.

on the up and up

I think just by looking at the raw data of my mood or the 7-day average, it’s clear that my emotional condition has trended positively over these past 3 years. But I think we might as well crunch the numbers since we got numbers to crunch.

While in theory I’d love for every day to be a “5,” that level of elation is not sustainable nor practical in the long term. Really, I want things to be at least “okay” or better. So I calculated the fraction of mood ratings over the previous 30 days that were greater than or equal to a “3”:

While there were several periods where that fraction was less than 50% (meaning that the majority of the mood ratings in the previous 30 days were worse than okay), none of those periods occurred in the most recent 16 months. In fact, there were several points where the fraction was close to 100%. Not bad. Literally.

My improved emotional state is also visible when we look at the distribution of my mood ratings in the first, second, and third+ years of my records. The histograms below show how many days had a particular average mood.5

The distribution of moods in year 1 had a peak at a rating of “3.5,” with a long lower tail and short upper tail. Year after year, the distribution tightens, indicating a tempering of my mood swings. While the peak-mood shifted down and up, my average mood has been up and up:

year 1: mood average of 2.7

year 2: mood average of 2.8

year 3+: mood average of 3.1

That’s great because feeling “okay” is defined as “3,” so not only have things improved, but—on average—things are better than okay. In fact, my emotional state got so good that I had a hard time finding things to complain about to my therapist.

Perhaps the most significant metric is how frequently I’ve had dangerously harmful thoughts. Generally, if I’m feeling kind of sour, I’ll record a rating of either 2.5 or 2. I only mark it down to a 1.5 if had any thoughts that things would be better if I wasn’t around.

So the number of ratings (of which there are two per day) that were between 0 and 1.5 inclusive are:

year 1: 90 (12% of ratings)

year 2: 40 (5% of ratings)

year 3+: 6 (0.8% of ratings)

I’d say that’s pretty pretty good.

future analysis

We’ve focused mostly on just mood, and largely ignored the many habits I’ve tracked. This leaves some questioned to be begged: What habits are most strongly correlated with better moods? What habits are correlated with each other? Is there some delayed or cumulative nature to the relation between my daily habits and mood? What about the frequency of my therapy sessions?

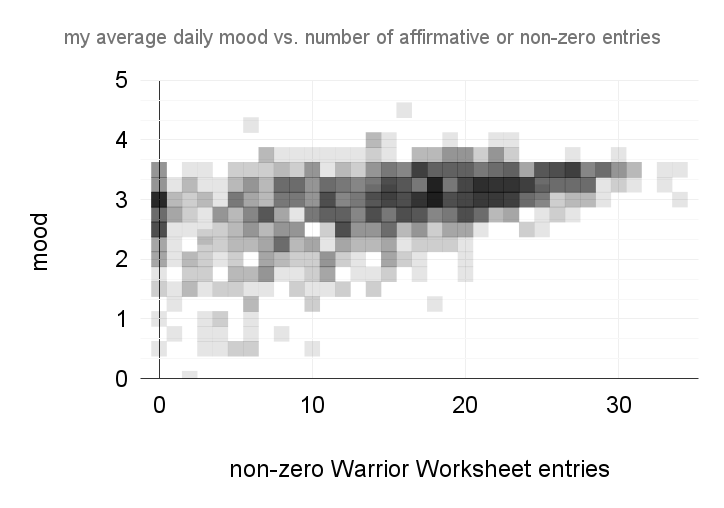

Lastly, I’ll share a scatter plot that displays how many habits I did do on a day, and the average mood for that day.

It’s curiously liver-shaped. What it tells me is that if my mood is relatively high (like 3.5), then I might have done a lot or a little of my habits. But, if I did a lot of habits (e.g. 30+) then my mood was certainly higher than average. Certainly, while these two measures are dependent on each other, it does give me a sense of agency that I can make choices that will make me feel better.

conclusion

It’s been said by many a wisemun that to achieve peace among others, one must first begin with peace within oneself—something I agree with heartily. I certainly don’t always have inner peace (as the entire essay above evinces), but I’m at peace with that. By tracking my habits for these past three years, I see clearly that life is a rolling journey and for there to be ups, there must be downs. But that mindfulness of behavior—with statistical significance—leads me to a more peaceful self.

The name for the Warrior Worksheet was inspired by the book King, Warrior, Magical, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine by Moore & Gillette. The book uses Jungian philosophy to develop archetypes that serve as models for healthy behaviors for men. I had recently read the book and felt that routines of mindful and physical habits were well aligned with “warrior energy,” hence the title of the spreadsheet. Also, I liked the alliteration.

Some exceptions to that include records for medicine consumption and my mood. That is, their values are not counted as yeses or noes.

The 7-day average is averaging 14 data points, as there were (usually) two per day.

I started taking 150 mg/day of bupropion. After 4 weeks of no effect, we increased my dosage to 300 mg/day (also with no effect). I tapered my dosage to zero over few weeks.

Note that because these are averages of the morning and evening ratings, and that ratings are on a scale with half-unit graduations, the averages fit nicely into quarter-unit bins.